Category: 2016

President’s Corner

by Ellen Colangelo, Ph.D., President of the San Diego Psychological Association

It hardly seems possible that this year is almost gone. It has been one of transition as we work toward a leaner and more efficient association. When we kicked off 2016 with a wonderful Meet and Greet, the year was like a huge canvas, waiting for Board and Committee members to create a montage that would enable us to build on our best assets. We have been working hard at this and seeing positive results.

It hardly seems possible that this year is almost gone. It has been one of transition as we work toward a leaner and more efficient association. When we kicked off 2016 with a wonderful Meet and Greet, the year was like a huge canvas, waiting for Board and Committee members to create a montage that would enable us to build on our best assets. We have been working hard at this and seeing positive results.

Our goals were to stabilize finances, the office, and membership. I am happy to report that we are achieving these goals. With advice from David Leatherberry, our legal consultant, we have moved from being employers to contracting with an employment agency. This has allowed us to reduce staff overhead to almost half of what it had been in prior years. Additionally, we have Crystal Thomas running our office 28 hours a week and providing a warm and welcoming presence to our 557 members. Our membership has increased, our expenses have decreased, and we are in a position to offer more of what we hear our members asking for: social networking events, a more user-friendly website, expanded CE opportunities, access to free legal advice, ethics consultations, an online, printable San Diego Psychologist, and many more services. In January, we will launch our new website mediated by Wild Apricot, a top-rated membership management software programs in the country.

Thanks to the Mission and Vision Committee’s efforts, we are creating an Association that utilizes the expertise of Board and Committee members so that we may be more efficient, financially stable, and better managed, without placing all the responsibility on a few members. Annette Conway and her committee are revising our Policies and Procedures Manual that has not been updated in several years. We are making many changes while building onto our best assets.

Another area of growth for us this year has been the collaboration we have had with other mental health providers. We are working with our mental health allies “to promote the profession of psychology and to serve the public” (SDPA Mission Statement). The annual, free event at beautiful Balboa Park brought together SDPA, CAMFT, UCSD Community Psychology, and SDPS for a free networking event that drew the largest number since its inauguration.

We continue this collaboration by offering member rates to the Mental Health Collaborative for our annual conference and having the Pacific Region of the American Association of Pastoral Counselors meet in conjunction with us for their annual conference. Beginning with the pre-conference social event and continuing with a full day of presentations on the theme of resiliency and mindfulness, the conference this year promises to be an excellent contribution to our field and professional development. The current issue of The San Diego Psychologist focuses on resiliency and mindfulness to complement the theme of the conference.

I feel so proud to be part of a Board that has committed so many hours and accomplished so much. I am grateful to our membership for entrusting me with the leadership position of President this year. I have learned so much about myself, and have had the opportunity to meet and work with amazingly bright and professional human beings. I hope that many of you will get involved in a leadership and/or committee role in SDPA and experience the joy of contributing to the future of our profession.

With gratitude,

Ellen

Editorial

by Gauri Savla, Ph.D.

by Gauri Savla, Ph.D.

Dear SDPA Members and Guest Readers,

I would like to start by thanking you for your overwhelmingly positive feedback on the maiden issue of online The San Diego Psychologist that we launched in May. We are especially thankful for your constructive criticism, which we have made every effort to incorporate in this current issue. Please continue to send us emails at TheSanDiegoPsychologist@gmail.com or directly comment on the articles online.

Since the publication of the Spring/Summer 2016 issue of The San Diego Psychologist, there have been a couple of new staff additions. I have had the distinct pleasure of working with our talented Newsletter intern, Sridhar Rao over the last few months. Sridhar has served as assistant to the Editor, website manager, proof-reader, and copy-editor. His unique background as a journalist with a technical background and current graduate student of Technical Communication at the University of North Texas makes him ideal for this job. The other addition to the team, of course, has been Crystal Thomas, the new SDPA office administrator, who has hit the ground running since the day she began. The current issue of The San Diego Psychologist is better because of these two people.

The theme of this Fall 2016 issue is Mindfulness and Resilience. Ellen Colangelo, the current President of the San Diego Psychological Association chose this topic to complement the October 1st 2016 Annual Fall Conference with the same theme. Thank you for responding so enthusiastically to our call for articles. Five of the best submissions make up the content of the Fall 2016 issue.

“Rise” by Alicia Dunn

I can trace the beginning of my own insights into the potential of mindfulness as a powerful tool for emotional and physiological regulation to a single moment in my doctoral training. As a predoctoral fellow at the University of California, San Francisco, I attended a talk by Dr. Robert Sapolsky, world-renowned neuroscientist, primatologist, author, speaker, and endowed chair and professor of neurology and neurosurgery at Stanford University. Dr. Sapolsky speaks and writes extensively about stress, and the quote that stood out to me from his talk was this:

“If I had to define a major depression in a single sentence, I would describe it as a “genetic/neurochemical disorder requiring a strong environmental trigger whose characteristic manifestation is an inability to appreciate sunsets.”

That last bit resonated with me deeply; it described every person with anxiety or depression that I had come across in my clinical training until then. Dr. Sapolsky was referring to mindful awareness without using the phrase itself.

I have been fascinated with how, in an age marked by unprecedented advances in medicine, people are no longer afraid of dying of diseases such as cholera or scarlet fever, or typically, influenza, but instead, are dying of diseases caused by prolonged, accumulated stress. As Dr. Sapolsky wryly remarks in his book, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, “…we are now living well enough and long enough to slowly fall apart.” Indeed, in my own clinical practice that focuses on geriatric patients, I see the effects of long-term, accumulated stress first-hand. I also get to see how mindfulness, either learned through therapy or a conscious lifestyle choice, helps some people prone to depression appreciate life despite their emotional pain. In today’s world, stress is ubiquitous, and so is anxiety and depression in varying levels; so much so that we have come to expect stress and its repercussions as “normal.”

The authors who have contributed to this Fall issue of The San Diego Psychologist are here to underscore the fact that it needn’t be so. There are gentle, effective tools to reverse the course of stress-related illness. In the last ten years, empirical research has demonstrated the benefits of mindfulness on both emotional and physiological resilience. Mindfulness has been an effective psychotherapeutic technique for people suffering from PTSD, generalized anxiety, and pain. It has been shown to lower blood pressure, boost the immune system, and even change brain structure and function. More and more clinicians and lay people are embracing this powerful tool to find peace and meaning in their lives.

Southern California is lucky to have excellent resources for mindfulness training that may be accessed via the Community Resources section of this issue.

In this issue of The San Diego Psychologist, we are lucky to have contributions from five experts on mindfulness and resilience. Linda Graham is a marriage and family therapist, a world-renowned expert on building resilience, and the keynote speaker at the SDPA Fall Conference to be held on October 1st, 2016. Her article focuses on the development of resilience over the lifespan, and how one can build resilience later in life. Dr. Shea is a clinical psychologist who has a mindfulness-based private practice in San Diego; she has a written poignant and powerful narrative of how mindful awareness helped build her resilience to face personal heartbreak. Dr. Tayer is a geropsychologist who has also written a first-person account of the how she found a unique way to build her own physical and psychological resilience. Dr. Hickman is the Executive Director of the Center for Mindfulness at the University of California, San Diego; his essay is on the symbiotic relationship between self-compassion and mindfulness. Finally, Dr. Stoddard, an expert on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and the Director of The Center for Stress and Anxiety Management has written an informative essay introducing ACT, with examples of practical exercises that it entails.

I hope this issue has been as insightful for you as it has been for me.

Please share your feedback in the comments below, or email me at TheSanDiegoPsychologist@gmail.com. As always, we encourage contributions from members of the SDPA; to submit an article, please refer to these submission guidelines.

Thank for you reading.

–Gauri

Mindfulness, Self-Compassion and Resilience

by Linda Graham, LMFT

Resilience is an innate capacity in the brain that allows us to face and deal with the challenges and crises that are inevitable to the human condition. It allows us to respond flexibly to external events, even those that are upsetting, disturbing, and stressful. It also influences our response to internal perceptions or schemas we have about those events, and how we see ourselves in relation to those events.

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for the broad range of cognitions known as executive function in the brain. We rely on it to regulate the body and the nervous system, quell the fear response of the amygdala, manage a broad range of emotions, attune to ourselves and to other people, empathize with ourselves and other people, develop self-awareness, and respond flexibly, i.e., shift gears, shift perspectives, and shift behaviors when necessary (neurobiologist and mindfulness expert, Daniel Siegal, M.D. was among the first to attribute flexible responding to the prefrontal cortex.)

The development and maturation of the prefrontal cortex is kindled in our earliest interactions with our first primary caregivers, typically our family of origin.

A mature prefrontal cortex allows us to analyze, plan, make judgments, discern options and make wise choices. This region of the brain develops as a result of our interactions with other people. We learn from others how to regulate our reactivity when we are startled, frightened, frustrated, worried, confused, to perceive whether we are in danger, or whether we are safe in connection with another human being. We also learn from our interactions, how to calm ourselves down as well as how to activate and motivate ourselves when necessary. We learn to attune to ourselves and to others by being attuned to by others.

The development and maturation of the prefrontal cortex is kindled in our earliest interactions with our first primary caregivers, typically our family of origin. Infants learn how to regulate their emotions by the emotions of their parents. Similarly, they learn that they have value and worth because the parents relate to them as valuable and worthy. They also learn to trust their competency in relationships by being related to in resonant, predictable ways. When these interactions go well, the infant, and later, toddler, and older child learns to be resilient, e.g., when he or she handles a disappointment in school or has difficulty playing with other children. With support and resources, he or she can even bounce back from a potential disaster like a parent becoming gravely ill or parents divorcing.

If these early interactions, and subsequently, the initial conditioning and wiring of the brain’s neural circuitry have not gone so well, the developing child’s patterns of coping can become defensive, rigid, and closed to new experiences, new people, new emotions, and new learning. Psychologist Bonnie Badenoch refers to this lack of flexibility as “neural cement.”Alternatively, the developing child’s patterns of coping lack stability, wherein the sense of self remains amorphous, inchoate, and their ability to cope, chaotic or volatile. The brain, in this case, is too flexible, and Dr. Badenoch’s terms, a “neural swamp.”

However, resilience can be learned as the growing child has interactions with other people such as siblings, peers, teachers, coaches, romantic partners, therapists, and spiritual teachers. A fully mature prefrontal cortex, the “CEO” of resilience, is the best buffer we have against stress, trauma, and later psychopathology.

Psychotherapy offers many tools and techniques, through many modalities, to strengthen the functioning of the prefrontal cortex and thus our capacities of resilience. The focus of this article is on the practices of mindfulness and self-compassion, two powerful agents of brain change well documented in research, that allow us to rewire our brains in ways that are safe, efficient, and effective. Both practices help us create the shift in our brains that help us make a shift in our responses to both personal suffering and suffering that we experience as part of the collective human condition.

Mindfulness simply brings awareness to our experience; an awareness of what is actually happening, as well as how we react to it. Self-compassion brings acceptance to our experience; an acceptance of what is actually happening, as well as our reaction to it.

Self-compassion involves bottom-up processing, i.e., body-based and emotion-based practices that shift the focus of the brain from our automatic survival responses or the automatic negativity bias of the brain and into a more open, receptive brain state.

Mindfulness involves top-down processing, i.e., conscious awareness and reflection that leads to wise choices and wise action.

Mindfulness and self-compassion accomplish this shift in the functioning of the brain in two very different ways. Self-compassion involves bottom-up processing, i.e., body-based and emotion-based practices that shift the focus of the brain from our automatic survival responses or the automatic negativity bias of the brain and into a more open, receptive brain state. This receptive brain state then allows us to shift behaviors.

Mindfulness involves top-down processing, i.e., conscious awareness and reflection that leads to wise choices and wise action. With mindfulness, our focused attention on what is happening and our reactions to the same shifts the focus of the brain from its default network that is responsible for worry and rumination. The default mode of processing can hinder wise coping and effort by getting us mired in memory after memory that leads to even more upset and suffering. Mindfulness, i.e., paying attention to our experience in the moment, moment after moment, facilitates the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, the structure of the brain we use most for self-awareness, for regulating the revving up and the shutting down of the nervous system, to quell the fear response of the amygdala, as well as for response flexibility, coping, good judgment, planning and decision making, and wise action and resilience.

When we are mindful,

- We pause and become present: We come out of distraction, dissociation, and denial. We show up and engage with the experience of the moment.

- We notice and name our experience: Labeling our experience activates the language centers of the brain and our higher conscious brain is online.

- We step back, disentangle from the experience, and reflect on it, cultivating a witness awareness.

- We can then, if we choose, monitor our experience and modify it. We can begin to make choices about how to respond to this experience.

- We practice shifting our perspectives, even knowing that we have a perspective.

- This allows us to truly discern options and even the potential consequences of our options.

- Then we can indeed choose wisely; we can let go of the unwholesome and cultivate the wholesome.

Self-compassion operates differently. When we pay attention to ourselves as the experiencer of the experience and bring kind, loving awareness to ourselves, we activate the care-giving system in the brain. This process activates the release of oxytocin, the hormone that is the immediate antidote to the stress hormone cortisol. Oxytocin puts the brakes on the body-brain’s automatic survival responses of fight-flight-freeze or shutting down, numbing out, collapsing, and allows the brain to re-open into a larger perspective, a bigger picture where we can reliably, realistically, and reasonably create a shift.

Compassion is one of a dozen positive, pro-social emotions that have been studied by behavioral scientists as well as neuroscientists for the last 20 years, along with gratitude, kindness, generosity, joy, awe, delight, and love. Self-compassion is especially potent because it activates the care-giving system and moves us to act, care, and protect. Researchers have found that daily practices of these positive, pro-social emotions have many benefits, a few among which are:

- Less stress, anxiety, depression, loneliness

- More friendships, social support, collaboration

- Shift in perspectives, more optimism

- More creativity, productivity

- Better health, better sleep

- Longer lives, by 7-9 years, on average

Resilience is a direct outcome of these practices. More compassion leads to more resilience.

In therapy, we cultivate the capacities of self-reflection, the observing ego, and the witness awareness as essential tools of therapeutic change. Whether we call it mindfulness or not, we ask our clients, “What are you noticing now?” When there is a shift in body posture, an upwelling of an emotion, an opening to a new area of inquiry, or a resistance to an area of inquiry, we ask them to pause and notice, and reflect on their experience, thus taking the time for any shifts or any insights to appear. This practice can often lead to meta-awareness, i.e., being aware of their awareness itself. Awareness is essential to being able to shift perspectives and views, notice that we have a perspective in the first place and a belief that is filtering our perception. Awareness, therefore, allows us to choose a response.

Awareness, conscious, intention reflection, is essential for the brain to do its rewiring, to shift old views, old perspectives, and create new views, new perspectives. The brain learns from experience. We learn from reflecting on that experience.

Richard Davidson, whose Center for Investigating Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has generated much of the data demonstrating the impacts of mindfulness and compassion practices on brain structure and brain functioning, says,

“The brain is shaped by experience. And because we have a choice about what experiences we want to use to shape the brain, we have a responsibility to choose the experiences that will shape the brain toward the wise and the wholesome.”

In therapy we use mindfulness to pause, notice, step back and reflect, then to monitor and modify our behaviors, to shift perspectives and discern what our options might be. We help clients choose the experiences that will shift the functioning of the brain and their coping behaviors toward the wise and the wholesome.

In therapy we use the practices of compassion and self-compassion, our compassion and caring, our attunement and empathy for the client, and their self-compassion and caring, their self-attunement and self-empathy, to cultivate self-acceptance. Self-acceptance is what puts the brakes on the shame attacks, the panic attacks, the rage attacks, and allows the clients to come into a larger, broader perspective again, to be resilient.

Carl Rogers said 50 years ago, “The curious paradox is, when I accept myself exactly as I am, then I can change.”

The Mindful Self-Compassion phrases, which I teach in my clinical sessions, create the space for that shift into self-acceptance:

May I be kind to myself in this moment.

May I accept this moment exactly as it is.

May I accept myself in this moment, exactly as I am.

May I give myself all the compassion I need.

Self-compassion is the most powerful tool for self-acceptance. With mindfulness and self-compassion together, the outcome is the client’s self-awareness, self-acceptance, learning and growth, change and resilience.

Linda Graham, LMFT, is an experienced psychotherapist and mindful self-compassion teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area with specializations in attachment trauma and post-

Linda Graham, LMFT, is an experienced psychotherapist and mindful self-compassion teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area with specializations in attachment trauma and post-

traumatic growth. She is the author of Bouncing Back: Rewiring Your Brain for Maximum Resilience and Well-Being, winner of the 2013 Books for a Better Life award and the 2014 Better Books for a Better World award. She publishes a monthly e-newsletter, Healing and Awakening into Aliveness and Wholeness and weekly Resources for Recovering Resilience, archived at www.lindagraham-mft.net.

Print a copy of the article here.

The Day I ‘Truly’ Received my Son’s Diagnosis of Autism: How Acceptance Led to Resilience

by Shoshana Shea, Ph.D.

Daniel Gottlieb was a young, burgeoning psychologist, husband, and father when quadriplegia entered his life. He was driving on the freeway when he was struck by a giant wheel that unhitched from a tractor-trailer, flew across the freeway, and crushed his car. He was instantly paralyzed from the neck down. As he lay in the hospital contemplating how he could end his pain and suffering, one of his night nurses, who suffered from depression and had heard that Gottleib was a psychologist, shared that she felt suicidal. Unaware that he had been contemplating that very idea himself, they talked through the night. Now, a prominent writer, therapist, and radio talk show host, he acknowledges that by listening to her experience, Gottlieb may have not only saved her life, but she likely saved his: Why? Gottleib says that the nurse saw him as a person. We become identified with the waves and we forget that we are the ocean (Brach, 2012). When the waves thrash us around, we suffer. Gottlieb later shared in two of his books, Letters to Sam and The Wisdom of Sam that he stopped striving to be the man he always wanted to be and finally realized the man he was.

I will never forget when one of those waves came into my life on a crisp, fall day in November. When picking up my son from preschool, his teacher told me to call his pediatrician because there was “something wrong” with him. Those words numbed me; I wondered out loud, “And what should I tell the doctor? That something was just wrong?” Indeed, when I spoke with the doctor, I catatonically echoed the preschool teacher’s words, “There’s something wrong with my son.” I might have said what I feared, “I did something wrong”. The doctor responded by saying, “Well, we all worry about the big ‘A,’… autism, that is.” I don’t remember much more of that day; the specifics are a blur to me now. I was completely submerged under the wave, being dragged along the ocean floor. Coming up for air was a long way off. This felt like a tsunami to me, and I had already counted myself a casualty.

…a “false refuge”; a tool that is seemingly helpful and certainly available, but which is not.

To use a metaphor from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), picture a man trapped in a deep hole, with only a shovel by his side. In despair and desperation, he picks up the shovel and begins to dig. Not being one who quits, he puts all his effort into digging his way out. He toils through the night and as the sun rises, he takes stock of his progress. He is not only still stuck in his hole, but it is deeper than he ever would have imagined. He is baffled; why was the shovel there if it was not a means to get out of the hole? He thinks, “This is all I have…” Tara Brach, clinical psychologist, author, meditation teacher and dedicated leader in training therapists to integrate mindfulness into their practice of psychology, calls this a “false refuge”; a tool that is seemingly helpful and certainly available, but which is not. The first thing the man must do is drop the shovel, and yet he fears he cannot because what would he do then? Sit in the darkness and the pain of being in a terrifyingly deep hole?

In her book, When Things Fall Apart, Pema Chodron writes, “Reaching our limit is not some kind of punishment. It’s actually a sign of health that, when we meet the place where we are about to die, we feel fear and trembling. A further sign of health is that we don’t become undone by fear and trembling, but we take it as a message that it’s time to stop struggling and look directly at what’s threatening us…How we stay in the middle between indulging and repressing is by acknowledging whatever arises without judgment, letting the thoughts simply dissolve, and then going back to the openness of this very moment. That’s what we’re actually doing in meditation. Up come all these thoughts, but rather than squelch them or obsess with them, we acknowledge them and let them go…We can meet our match with a poodle or with a raging guard dog, but the interesting question is – what happens next?”

Art by Amrit Khurana, 2013

When I initially received my son’s diagnosis, I did more than my fair share of shoveling; I went through shock, anger, guilt, shame, reasoning, begging, pleading, bargaining, blaming, rage, numbing, and most of all, rigorous inquisitions of myself. If the shovel had not worked before that point, I was not going to let my son down, so I shoveled harder, with more gusto than ever before. It would take me six months until I finally stopped digging when the RAIN began to fall. The RAIN soaked my body and I bathed in my pain and tears.

It would take me six months until I finally stopped digging when the RAIN began to fall.

I attended a workshop led by Tara Brach as part of a conference on Mindfulness (FACES, 2009). Dr. Brach led us through an exercise where she asked us to take something we were struggling with in our lives and say “Yes” to what we were experiencing. She elaborated, “Saying ‘Yes’ does not get rid of the pain; it actually allows the experience to be freed and unfold itself; a space opens up. Some people notice fear, however, and do not get that sense of freedom. When we get stuck, it usually means we have not looked deeply enough into the nature of our experience…”

The acronym RAIN has been used in mindfulness to engage in a progressively deepening process:

R stands for recognize: “What is going on? What are we noticing?” “They say there is something wrong with my child, or, maybe not?” “He seems alright…” This process involves also recognizing equivocation.

A stands for acceptance, wherein we allow the situation to simply be. Without knowing it, we often say, “This can’t be happening.” With acceptance, we say “Yes,” and allow it to be. But I didn’t want to say “Yes.” I was saying “No! This can’t be happening; this can’t be happening; this can’t be happening…” It was like if I admitted there was “something wrong,” I was signing up my son for never having a “normal” life. I was giving up on him. If I truly accepted his diagnosis, maybe it didn’t have to be that something was “wrong”; maybe it just was.

Acceptance is bending down and picking up the ball and holding it close to our bodies.

Another ACT metaphor is that of a ball and chain attached to our ankle. Burdens are cumbersome, often shameful, their weight unbearable. So we tend to act like they do not exist, and valiantly try moving forward in our lives. We try and drag our ankle but it just won’t budge. We tell ourselves, “I can’t be having this pain; more importantly, I won’t allow it!” So we stay stuck. Acceptance is bending down and picking up the ball and holding it close to our bodies. This way¸ we will likely move at a very slow pace, but at least we are moving. Jack Kornfield reminds us of the Zen Buddhist saying in his book, The Wise Heart, “If you understand things are just as they are. And if you don’t understand things are still just as they are.”

I stands for investigate our inner experience with heart, with kindness, with compassion. We use the Four Foundations of Mindfulness to further deepen this investigation (Mind, Body, Feelings, and Dharma, Kornfield, 2008).”

- Mind: We ask, “What am I believing? What am I really afraid of? What is most distressing to me?” “What stories or judgements do I have about this?”, “I failed him.”

- Body: “Where do I feel this in my body?” My head aches. My chest is tight. My stomach is churning.

- Feelings: Agitation, sorrow, and fear.

- Dharma: ”The elements and the patterns that make up experience” (from The Wise Heart), “ How locked in are we?” “What would I see if I were to go beyond this small self?” But I can’t come into my present moment because it won’t be OK; he won’t be OK. I won’t be OK. Pema Chodron says, “We can meet our match with a poodle or a raging guard dog, but the interesting question is – What happens next?”

This leads us to the final step of RAIN.

N stands for non-identification or non-attachment. We see our thoughts as thoughts, and not as who we are as a person. In ACT, this is called “defusion.” Tara Brach ended the exercise with the following words: “We unhitch ourselves, and we come home to who we really are. We are fully present. No longer identified with the small self. Back to natural loving presence. And we are then able to really ask ourselves, ‘So what am I needing in this moment?’”

I would perseverate, equivocate, and hide in silence and drown in self-pity. In the end, I came to realize that I was completely unwilling to accept that this was indeed happening.

Before going through these steps of RAIN, I really thought I was accepting the situation. I had taken my son for a private evaluation. I was calling professionals to figure out whether I really needed to intervene. I was fighting against well-meaning friends and family, by telling them that he needed to be assessed, and they would push back and tell me to just leave him alone and that he would grow out of it. They would then contradict themselves by looking worried at other times, and asking me if I noticed he was doing something that other kids don’t normally do. I would perseverate, equivocate, and hide in silence and drown in self-pity. In the end, I came to realize that I was completely unwilling to accept that this was indeed happening. This lack of acceptance was impeding my process of resilience, and the ability to truly help myself and my son. I was never going to drop that shovel, and then, I did.

Resting in my awareness, I was able to let go of the struggle; my exit strategies had become defunct, and the tears flowed freely. At the next break, I stepped out and called the school district to schedule an evaluation to arrange for intervention. I haven’t looked back since. It is not that I haven’t indulged in self-pity or other avoidance strategies since then; it is that I always return to the truth and come back home to natural, loving presence. I am willing, and I have dropped the shovel. My son has been one of my greatest teachers and remains so.

If you can rest in the ocean, you are not afraid of the waves (Tara Brach).

References

Brach, T. (Producer). (2012, March 7). Freedom in the Midst of Difficulty. Retrieved from URL https://www.tarabrach.com/freedom-in-the-midst-of-difficulty-audio/.

Brach, Tara. (2012) True Refuge: Finding peace and freedom in your own awakened heart. New York, NY: Random House Publishing Group.

Chodron, Pema. (1997) When Things Fall Apart: Heart advice for difficult times. Boulder, CO: Shambhala.

FACES Conference (2009, April 2-4) Awakening to Mindfulness. La Jolla, CA.

Gottlieb, Daniel. (2006) Letters to Sam: A Grandfather’s lesson on love, loss, and the gifts of life. New York, NY: Sterling Publishing Co.

Gottlieb, Daniel. (2010) The Wisdom of Sam: Observations on life from an uncommon child. Carlsbad, CA: Hay House.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guildford Press.

Kornfield, Jack. A Wise heart: A guide to the universal teachings on Buddhist psychology. New York, NY: Bantam Dell.

Dr. Shoshana Shea has a full time mindfulness-based and cognitive-behavioral therapy practice in San Diego for life transitions, anxiety, and stress. She received her Ph.D. from the San Diego State University/University of California San Diego (UCSD) Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology and has over 20 years of combined experience at UCSD, the Veteran’s Administration hospitals, in research, and in clinical practice. For more information, the website address is http://shoshanashea.com/.

Print a copy of this article here.

Resilience Reconsidered

by Wendy Tayer, Ph.D.

Written in consultation with Victoria Bilyeu, owner of Gyrotonic Solana Beach

Resilience is a measure of our coping elasticity, our ability to bounce back from adversity, acute stress, unexpected traumas and life’s surprises. As psychologists, we are acutely aware of relative and varying degrees of resilience in ourselves, our family members, friends, colleagues and patients.

Resilience is a complicated construct because it encompasses not just cognitive flexibility and the ability to regulate our own emotional states but our bodily self as well. Our overall “elasticity” can be perceived in our body language. We observe this quality in our patients in intake interviews, and over the course of therapy, looking for indicators of healthy behavior change. It is well documented by the DSM, ICD-10 and numerous measures of anxiety and depression that these disorders are characterized by a compressing of the self, cognitively, emotionally and physically. People who have anxiety often feel constrained by the repetition of anxious thoughts, obsessions, compulsions or just plain worry. People who struggle with major depression experience a shrinking mental world characterized by social isolation and hopelessness wherein often, there is no emotional peripheral vision. Among the physiological correlates of these disorders are tight, tense muscles, gastrointestinal distress, fatigue, anergia, shortness of breath, and heart palpitations. Anxiety and depression often present together, like two sides of the same coin, at times compensating for each other. These sensations signal a loss or lack of homeostasis in our system. We feel off kilter, especially if we are not accustomed to feeling stressed. Recent neuroscience research validates this finding. Poor integration of some aspects of the self are correlated with psychopathology, and healthy integration of other aspects are correlated with psychological wellness. (Siegel, 2010)

These sensations signal a loss or lack of homeostasis in our system. We feel off kilter, especially if we are not accustomed to feeling stressed.

Let me illustrate this last point with a first-person account.

I think of myself as a resilient person. But as I get older, I find that my mettle is tested by various facets of my daily life: 1) I am undergoing peri-menopause, 2) I have a teenager living at home, 3) my children still need me in various ways, whether to edit college essays or to strategize how to juggle academic loads, 4) I have friends who lean on me for social support, whether to process their difficulties finding a job or the recent cancer diagnosis of a family member, 5) I am available to family members who are aging, sick, grieving, to help shoulder their burdens. It is an interesting phase of life; there are many joys, and yet, a whole new set of challenges in terms of mood, sleep, irritability, pain symptoms and weariness.

Some of these challenges began presenting themselves a few years ago. I still recall vividly the words of my long-time gynecologist at the time: “Your days of restorative sleep are officially over. Start taking something for your mood and sleep and get a monthly massage…” I have been aware that I needed a new strategy to “fill up my tank,” as it were, since then, but I did not understand what that meant until one recent, serendipitous, ultimately transformative experience.

I am a rather adventurous person who leaves no stone unturned when visiting a place or on vacation. I have to check out everything! For instance, I am the kind of person who feels compelled to explore entire museums and read every descriptor board at an exhibit. This curiosity and zest for learning recently paid off in a huge way; I discovered a new way of being in my body that psychologically benefited me in unique ways unmatched by any other practice or physical activity. In my effort to find a practice that would be energizing or restorative, I had tried yoga, Pilates, running, none of which have felt right for me. In fact, they often left me in pain or gastrointestinal distress.

Art by Frank Morrison

…I felt myself becoming increasingly energized and balanced, while also free and restored. I left the class with a tremendous sense of release and felt six inches taller, an extraordinary, unexpected experience.

Last February, while away on a vacation with my mom, the spa where we were staying was hosting Gyrokinesis week. I had never heard of Gyrokinesis, but curious and game to try new things, as always, I jumped at the opportunity. My introductory class, comprised of 40 women, was led by Gina Muensterkoetter, a dynamic and gifted instructor who happened to be the partner of Juliu Horvath, the founder of Gyrokinesis. It may sound hyperbolic (and certainly out of character for me), but I experienced this woman as akin to an actual, living goddess. As she led us through 75 minutes of undulating, fluid, dance-based body movements that used the spine and sternum to lead the rest of the body, I felt myself becoming increasingly energized and balanced, while also free and restored. I left the class with a tremendous sense of release and felt six inches taller, an extraordinary, unexpected experience. Gina explained that gyrokinesis creates energy rather than expending it as with traditional aerobic exercise. I attended the class every day for a week and could palpably feel the shift in my body. I felt elongated, energized and renewed. In fact, I was likely radiating these sensations outwardly because Gina seemed to sense it; she remarked that energy was almost overwhelming. Her feedback was tremendously validating!

I was determined to find a class or instructor where I live, and that is what I found with one phone call: Victoria Bilyeu, owner of Solana Beach Gyrotonic. We connected instantly and found that we shared similar philosophies about healthcare and healing even though we had been trained in very different traditions and modalities. I have been working with her since March, and my body has been in better shape these past few months than it has been in recent years. This practice also has improved my overall resilience in coping with increased work demands and ubiquitous parenting challenges. I also am more available to my friends and family who lean on me, and I can be supportive without it becoming an emotional burden. According to Victoria: “Pain is similar to a riptide, and doing Gyrotonic is like paddling on top of the crest of the wave to ride through and release it…it’s the only [exercise] modality out there that makes your body better with age or time spent [doing it].” I hope you are as intrigued as I was and continue to be.

So, what is Gyrokinesis? Gyrotonic and Gurokinesis are related methods that were invented by Juliu Horvath, a former professional ballet dancer, in an effort to heal himself after debilitating dance-related injuries. Gyrotonic utilizes versatile equipment to restore balance and agility, but with more intensity than Gyrokinesis. According to an interview with Gina Muensterkoetter, gyrokinesis and gyrotonic focus on circular and spiralling movements which mirror cellular and underlying joint patterns of figure eights. The theory behind these methods is that the parallel movements create connections that help to restore and balance the body. Juliu Horvath’s philosophy is predicated on training to be one’s own teacher solely through learning to be with one’s own body. Much of the focus is on connecting with oneself and with others in the process. That connection was palpable in the room with Gina as I can attest to firsthand.

As a health and gero-psychologist who is trained to study and observe the mind-body relationship, this practice and experience was transformative for me. I had found a partial solution to my peri-menopausal experiences that had in turn, challenged my resilience. For me, the most dramatic element of the practice is the way it is focused on releasing joints, muscles, and the spine. We spend a lot of time in psychotherapy discussing cognitive strategies for restructuring our thoughts, processing our feelings, trying to understand why we do things and how to effect change. But we don’t do a lot with movement other than diaphragmatic breathing or body scans, even in behavioral medicine which highlights mind-body relationships in theory and practice. I have found Gyrotonic and Gyrokinesis to be potent strategies for decompressing stress. The releasing aspect of the Gyrotonic expansion program seems to be a fitting antidote to the compression associated with life stressors, chronic anxiety and depression.

Routines and habits are adaptive, but so is cognitive flexibility. I tell my patients that they can heal from the inside out or the outside in. Having found a new modality for myself delivers a sense of renewal and strengthens this belief.

Other people see mental health professionals as helpers, caregivers, problem—solvers because of what we do and our role in the world as healers; I often find that others look to me me for advice, guidance, and direction, and often, as an empathic shoulder to lean on. My current job includes outpatient psychotherapy and supervision of graduate students, but also on-call work for the ER and hospital floor consults. These multiple demands sometimes are overly taxing to me emotionally and cognitively, not to mention physically. In sharing my experience with other women in healthcare professions, it seems that my experience is not unique. So, the question becomes a matter of how we manage or maintain our resilience over time. We as psychologists learn early on that we have to prophylactically take care of our emotional selves, develop professional boundaries, find ways to recharge our emotional batteries when we feel depleted and develop routine self-care routines. We strive to be competent, efficacious role models to our patients, students, children and colleagues. It seems to me that these tasks and responsibilities can be difficult to uphold over time, or need rethinking when the usual self-care regimen no longer suffices. Routines and habits are adaptive, but so is cognitive flexibility. I tell my patients that they can heal from the inside out or the outside in. Having found a new modality for myself delivers a sense of renewal and strengthens this belief. In this vein, I encourage you to re-evaluate your methods of self-care and personal restoration, to seek integration of your own system, to open yourself up to new experiences and opportunities for learning, growing and building resilience.

References

Siegel, D. J., (2010). The Mindful Therapist. 2010. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

For more information on Gyrotonic and Gyrokinesis, see www.gyrotonic.com

Dr. Wendy Tayer is a Health Sciences Assistant Clinical Professor in the UCSD Department of Psychiatry. She is a health psychologist and a clinical supervisor, and her clinical practice specializes in gerontology, behavioral medicine and student health.

Print a copy of this article here.

Safely-Challenged: Self-Compassion and Mindfulness Enhancing Each Other

by Steven Hickman, Psy.D.

This article appeared as a blog post on https://stuckinmeditation.com on August 12th, 2016

This morning, as I lingered outside the meditation hall before morning practice, I came upon the biography of E.B. White. I randomly opened the book and this is the verse that I found:

The critic leaves at curtain fall

To find, in starting to review it

He scarcely saw the play at all

For watching his reactions to it

The critic’s harsh voice comes from the outside in, can tangle us in overwhelm or just pummel us at the level of challenging. But we can find some refuge in the safety of the inner circle of moment-to-moment experience.

It helped me realize that the Inner Critic (like the Drama Critic) always dwells outside the “play” itself or outside of our direct moment-to-moment experience. That experience of each moment is the center of three concentric circles where that center circle represents safety, the next circle out represents challenge and the largest circle is overwhelm. The critic’s harsh voice comes from the outside in, can tangle us in overwhelm or just pummel us at the level of challenging. But we can find some refuge in the safety of the inner circle of moment-to-moment experience.

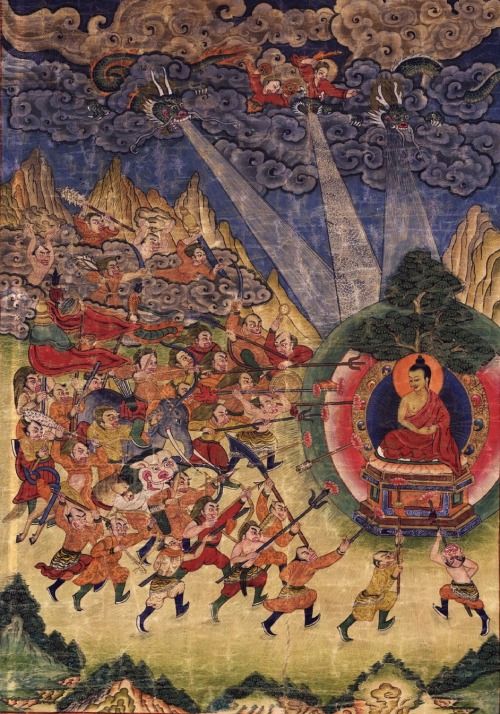

Art on cotton, 1800s

In fact, the area outside of the safe circle is really where we most often live our lives because this is where we connect with other people, encounter triumph, tragedy, love and loss.

It is here in this safe circle where we can find our feet, where we can be nourished by our own resources and become clear on our values.

So I think of mindfulness as learning how to find our safe circle and how to make our way back to the refuge of the present moment when we are caught in reactivity and suffering. It is here in this safe circle where we can find our feet, where we can be nourished by our own resources and become clear on our values. We all have different degrees of ability to return to that safe circle but we all have some capacity.

While “pure” mindfulness can give us refuge in the present moment, it can be dry and cold just living in bare attention of each moment in our safe place. We actually live at the edges of that circle or even beyond, and something in us is curious, wants to be connected and even wants to be challenged, if only in a small way.

Compassion by itself, disconnected from the wellspring of the present moment, can be kind and warm, but scattered, unfocused and in the end, unsustainable because it can’t be easily replenished.

By remembering that the critic lives in the space around the safety circle, we can be reminded that this is where our attention and our compassion should be directed if we seek change or relief.

When we bring compassion, and particularly self-compassion, to the practice of mindfulness then we actually gently expand the circle of safety into the area of challenge so that we can feel some ease in challenge, engaged in the sometimes messy (but also fulfilling) world of suffering, self-criticism, or the dragons that lurk beyond the charted territories of ancient maps. By warming up the conversation we can actually build ourselves a progressively bigger platform from which to live, that allows for a bit of permeability (if that’s called for) between safety and challenge. This new expanded presence can allow us to hear the inner critic, to invite in the wisdom of a compassionate being, or to consider the need that has not been met by others so that we can provide it to ourselves.

By remembering that the critic lives in the space around the safety circle, we can be reminded that this is where our attention and our compassion should be directed if we seek change or relief. We cannot dwell on the presence of difficult feelings or challenging other people if we want a way through our suffering. We can only tend to the relationship we have with the feelings or the people and how we can meet those unchangeable facts with some degree of warmth and kindness that can relieve the suffering in wanting things to be different than they are.

Dr. Hickman is a Clinical Psychologist and Associate Clinical Professor in the UCSD Departments of Psychiatry and Family and Preventive Medicine. He is the Executive Director of the UC San Diego Center for Mindfulness, a program of clinical care, professional training and research. Dr. Hickman is also the Executive Director of the non-profit Center for Mindful Self-Compassion, and a member of the Executive Committee of the UCSD Center for Integrative Medicine.

Print a copy of this article here.

The Use of Experiential Practice in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

by Jill A. Stoddard, Ph.D.

This article has appeared, in part, in Dr. Stoddard’s book, The Big Book of ACT Metaphors

Life is hard. It is painful. We want, we desire, we envy. We compare ourselves to others and see what they have that we don’t. We assume they are doing better, that they are happier. With these assumptions and social comparisons often comes anxiety, self doubt, despair, longing, or dissatisfaction. We assume these negative emotions are the problem to be fixed. We believe we are supposed to be more happy (like everyone else) and we consume books and blogs and videos to figure out how to fix sadness and be more happy (like everyone else).But sadness may not be the problem. After all, pain, whether physical or emotional, is universal; it is part of being human. Perhaps all the effort we expend trying to avoid, suppress, or “fix” pain is what really leads us to suffer. This premise lies at the heart of acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999).

Art by Elena Ray

Perhaps all the effort we expend trying to avoid, suppress, or “fix” pain is what really leads us to suffer.

What Is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy?

Acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT (pronounced as the word “act,” not the letters a-c-t) is a behavioral therapy that focuses on “psychological flexibility” or the ability to contact the present moment more fully (including all thoughts and feelings, no matter how difficult) and choose actions that are in line with personal values. The goal of ACT is not to feel better, but to do better and to live better.

ACT centers on identifying the thoughts and feelings that may be obstacles to valued living, and aims to change our relationship to those internal experiences, rather than changing the experiences themselves

Through six core processes—acceptance and willingness, cognitive defusion, present-moment awareness, self-as-context, values, and committed action—ACT participants are guided to open up and invite in all thoughts and feelings. ACT advocates opening to internal experiences not because there is some glory in feeling pain for pain’s sake, but because efforts to avoid painful feelings—for example by using drugs, socially isolating, or procrastinating—create suffering insofar as those efforts pull us away from things that are important to us and that contribute meaning and vitality to our lives. ACT centers on identifying the thoughts and feelings that may be obstacles to valued living, and aims to change our relationship to those internal experiences (through acceptance and mindfulness processes), rather than changing the experiences themselves.

Language and Suffering

Theoretically, ACT is grounded in the experimental work of Relational Frame Theory (RFT), which asserts that much of human suffering is attributable to the bidirectional and generally evaluative nature of human language (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001). RFT suggests that the unique capability of humans to respond to derived relationships is exactly what traps us in emotional suffering. Specifically, our abilities to plan, predict, evaluate, verbally communicate, and relate events and stimuli to one another both help and hurt us (Hayes et al., 1999).

Clearly, our higher cognitive abilities allow us to solve problems. For example, if you get a terrible haircut, you can go back to your stylist (or perhaps decide to see a new stylist) and get a different haircut. If you don’t like the color you just painted your walls, you can choose a new color and repaint them. At the same time, we often wrongfully try to apply these same skills to our inner experiences. We believe we should be able to control the way we think and feel in the same way we can control our hair and our houses. However, mounting research has demonstrated that the more we attempt to suppress thoughts and feelings, the more present they become (Abramowitz, Tolin, & Street, 2001; Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, & Hofmann, 2006). In addition, although these attempts to avoid our internal experiences (i.e., experiential avoidance) may appear to work in the short term, they ultimately lead to a more restricted existence. For example, a person who feels anxiety every time he enters a social situation may temporarily reduce his anxiety by avoiding interpersonal encounters; however, his ability to live life freely will become greatly limited, and his fear of social interactions will persist. Thus, the verbal rules we successfully use to solve many problems in the external world typically cause suffering when we attempt to use them to “solve” painful thoughts and feelings.

ACT stipulates that overidentification with literal language (taking the mind’s messages at face value and becoming fused with their content, rather than being guided by direct, present-focused experience) leads to psychological inflexibility and suffering. Through the six core therapeutic processes, clients learn to mitigate the impact of literal language, creating the wiggle room needed to take actions that are guided by personal values, rather than being driven by internal private events.

Thus, the verbal rules we successfully use to solve many problems in the external world typically cause suffering when we attempt to use them to “solve” painful thoughts and feelings.

Experiential Practice in ACT

If, however, language is at the core of human suffering, how can we use psychotherapy to alleviate suffering, given that the foundation of therapy is verbal dialogue? Of course there is no getting around the need to use oral communication. However, ACT attempts to circumvent some of the problems inherent in literal language by shifting away from traditional didactics and dialogue and moving toward a more experiential encounter. Through mindfulness exercises, clients are encouraged to observe and make contact with their thoughts and emotions as they occur, both in and out of session. In addition, the use of a wide variety of metaphors and experiential exercises is central to helping clients understand the approach in an experienced way, rather than intellectually.

Examples of Experiential Practice

Each of the six core therapeutic processes in ACT can be demonstrated through active practices designed to experientially teach that specific concept. What follows are selected scripts for metaphors and experiential exercises from The Big Book of ACT Metaphors: A Practitioner’s Guide to Experiential Exercises and Metaphors in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Stoddard and Afari, 2014).

Acceptance: Yes and No exercise (Walser & Afari, 2012, adapted from Brach, 2003)

“In this exercise, I’m going to ask you to avoid experiencing the sensations you have of your back against the chair you’re sitting in. For the next two to three minutes, whenever you notice a sensation of your back against the chair, I want you to say no to those sensations.” You can expand on this exercise by having the client first say no to the physical sensations of her back against the chair, and then say no to any thoughts and emotions that show up about the sensations or even the exercise more generally.

Once you’ve allowed enough time, refocus the client’s attention to the room. Ask her what sensations came up and what it was like to say no to these sensations. Help her distinguish between the physical sensations and the thoughts and feelings that accompanied resistance.

“Okay, now I’d like to do the same exercise, except now rather than avoiding the sensations of your back against the chair, I’d like you to be willing to feel those sensations, simply as sensations, whatever they may be, positive or negative: pain, discomfort, tingling, warmth, coolness, and so on. Whatever those sensations are, I’d like you to say yes to them.”

Again, ask her to describe the physical sensations and the thoughts and feelings that came up. Help her reflect on the difference in her experiences with saying yes and no as it may relate to willingness and control strategies.

Defusion: Fly Fishing metaphor (Whitney, 2013)

“Have you heard of fly fishing? A good fly fisher knows exactly what the trout are feeding on and ties up flies that imitate those insects. They are so good at this that the trout can’t tell the difference. They cast the fly into the stream right in front of the trout, and the trout sees it floating by, buys that the fly is real, bites it, and gets hooked.

Our minds can be like really skilled fly fishers. Our thoughts and feelings are like highly specific flies the mind designs—just the ones we’ll bite on. The mind casts them out on the stream in front of us, and they seem so real that we buy them, bite, and get hooked. Once we’re hooked, the more we struggle, the more we behave in ways that drive the hook in deeper and keep us on the line.

As we swim in the stream of life, there are flies floating by on the surface all the time. As we get better at spotting flies and recognizing that we don’t have to bite them, we get hooked less often and have more flexibility to swim in the direction of our values.”

Values: Heroes exercise (Archer, 2013)

“Think about your heroes. Consider people who have played a direct role in your life: family members, friends, teachers, coaches, teammates, and so on. Now think about people who have inspired you indirectly: authors, artists, celebrities, or even fictional characters. Who would you most like to be like? Pick one person you really admire.” (Give the client time to think about this.) “Now think about all the qualities you really admire in this person—not the person’s circumstances, but personal qualities—and write them down. Once you’ve done this, I’d like you to look this over and think about how these might translate into your own personal values.”

Discuss the specific qualities that come up. Clients might write things like “ambitious,” “selfless,” “generous,” “thoughtful,” “kind,” “compassionate,” “creative,” and so on. Ask clients how they think they are like this person or unlike this person, and in what ways they might like to move toward being more like this person. Help them identify the life domains (friendships, family, career, and so on) in which they might be willing to work on building these qualities. This can lead to a discussion of obstacles and how clients might use other ACT processes, such as acceptance, present-moment awareness, defusion, and self-as-context, to handle those obstacles in the service of moving forward in a values-consistent way.

Summary

ACT aims to increase psychological flexibility, or the ability to be present to all internal experiences and choose values-driven behavior. Getting “hooked” by thoughts and literal language threatens psychological flexibility and is at the core of human suffering. To bypass the traps of language, ACT relies on the use of exercises and metaphors to facilitate learning that is experiential rather than didactic. Therapists must take care to not over use experiential practice, and to tailor the exercises to each individual client. Applying these practices flexibly to address areas where clients are stuck and disconnected from personal values can provide a powerful therapeutic experience.

References

Abramowitz, J. S., Tolin, D. F., & Street, G. P. (2001). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression: A meta-analysis of controlled studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 683–703. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00057-X.

Campbell-Sills, L., Barlow, D. H., Brown, T. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2006). Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1251–1263. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.001.

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (2001). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Plenum.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

Stoddard, J. A., & Afari, N. (2014). The big book of ACT metaphors: A practitioner’s guide to experiential exercises and metaphors in acceptance and commitment therapy. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications

Dr. Stoddard is the founder and director of The Center for Stress and Anxiety Management, an outpatient clinic with three locations throughout San Diego county, specializing in evidence based treatments for anxiety and related problems. She is also an Associate Professor at Alliant International University. Dr. Stoddard specializes in the treatment of anxiety and related disorders and has expertise in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Print a copy of this article here.

Resources

The following is a list of resources compiled by Shoshana Shea, Ph.D. For reading recommendations, please refer to her article in this issue of the Newsletter.

***Please feel free to add to these resources in the comments section below***

Compassion by Arlene Dubo

Courses and Workshops

UCSD Center for Mindfulness

https://health.ucsd.edu/specialties/mindfulness/Pages/default.aspx

- Compassion and mindfulness programs (Mindful Self Compassion, Compassion Cultivation Training, and Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction)

Tara Brach

- On-line course on Integrating Meditation into psychotherapy and regularly offers courses through her website and mailing list

- Audio talks and meditations on various topics related to mindfulness

FACES Conferences

- Workshops and conferences on mindfulness and compassion

Association for Contextual Behavioral Science (ACBS)

https://contextualscience.org/

- The official ACT community’s association and website. Resources, a list of local ACT therapists, talks, information, and workshops on ACT

Praxis

https://www.praxiscet.com/events

- Continuing education and training opportunities to learn ACT

Podcasts

“The Self-Acceptance Project”

http://live.soundstrue.com/selfacceptance/

- A free project put on by Sounds True, comprising interviews with prominent leaders, researchers, and clinicians in the field of mindfulness and compassion. ourses and opportunities to learn mindfulness.

President’s Corner

by Ellen Colangelo, Ph.D., President of the San Diego Psychological Association

This is an exciting time as we launch the online edition of The San Diego Psychologist. Our new editor, Gauri Savla, has researched and designed the most user friendly way to publish the newsletter. You may agree that she has managed to retain the attractiveness and journalistic quality that we have enjoyed over the years in the hard copy versions.

This is an exciting time as we launch the online edition of The San Diego Psychologist. Our new editor, Gauri Savla, has researched and designed the most user friendly way to publish the newsletter. You may agree that she has managed to retain the attractiveness and journalistic quality that we have enjoyed over the years in the hard copy versions.

Historically, each editor has brought his or her own unique style and flavor to The San Diego Psychologist. This is what keeps it vibrant and alive and motivates us to want to read it.

Gauri’s intent as editor is to have a theme to each edition; She has selected Aging for the current, Spring/Summer 2016 issue. As the boomers move into the final quarter of their lives, we begin to see more and more of the Medicare crowd in our practices, struggling with the gradual decline of strength and flexibility, minor to major cognitive decline, financial concerns, loss, and spiritual challenges that come with the existential awareness of life as impermanent. As one who is in this generation of Elders, I look forward to reading this maiden, online edition of The San Diego Psychologist.

Congratulations, Gauri, on a job well done. Special thanks to our previous editors, especially Karen Fox, our outgoing editor, who continued the strong tradition of quality that is the foundation of this publication.

Meet the New Editor

by Brenda Johnson, Ph.D.

SDPA has been fortunate to have had many exceptionally talented Newsletter editors over its years. As this first online edition of The San Diego Psychologist launches, I am pleased and honored to introduce you to our newest editor, Gauri Savla. I have known Gauri for almost 13 years; I was among her first clinical practicum supervisors, and am now proud to call her my colleague and friend.

SDPA has been fortunate to have had many exceptionally talented Newsletter editors over its years. As this first online edition of The San Diego Psychologist launches, I am pleased and honored to introduce you to our newest editor, Gauri Savla. I have known Gauri for almost 13 years; I was among her first clinical practicum supervisors, and am now proud to call her my colleague and friend.

Gauri brings so much to the SDPA; Her academic achievements are significant. After graduating at the top of her class in her Clinical Psychology Master’s program at the University of Mumbai, India she attended the San Diego State University/University of California, San Diego Joint Doctoral Program, graduating with a second Master’s degree in 2006 and a Ph.D. in 2009. She went on to earn a National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry for her postgraduate studies at the UCSD Department of Psychiatry.

So far in her young career, Gauri has authored over 20 peer-reviewed papers and 10 invited book chapters. She has served as a reviewer for several journals, including the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and the British Journal of Psychiatry, and she has presented at numerous professional conferences. As a clinician, she has had years of experience providing individual and group psychotherapy in both outpatient and inpatient settings, and conducting neuropsychological assessments at UCSD Outpatient Psychiatry Services, VA Healthcare System San Diego, and the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute at UC San Francisco, among others.

Gauri’s primary professional focus and passion is working with seniors and their families. In 2014, she opened her private practice in Encinitas, specializing in geriatric psychology.

In 2005, as an SDPA student member, Gauri presented a workshop to our members on ways to improve power point presentations. Her task was challenging because the attendees’ computer skills varied wildly from “How do I turn on this laptop?” to “How do I add movie clips?” I recall Gauri clearly, concisely and very patiently taking each of us step-by-step through that process. She made the class a lot of fun and everyone left better informed.

Under her editorship, the San Diego Psychologist will enjoy the same professional focus and technical expertise Gauri brought to that workshop. She will welcome your contributions.

Dr. Johnson is a Past President and Fellow of the SDPA and a clinical psychologist in private practice.